The Stinging Sorority, Page 3

By S. F. AARON

I once knew a child of seven or eight to grab a big red hairy sand ant just as I had done long before; the youngster was eager to get the pretty thing for me. The little fellow's hand swelled greatly and there was a decided lethargy for a time, but within perhaps an hour it had passed away. I can hear the boy's howls yet and never can that child be induced to be an entomologist.

The much feared builder of the globular paper nest the white-faced black hornet, Vespa maculata has been too much publicized. It is a fighter, but not very poisonous. Who frequenting the out-of-doors has not encountered with considerable trepidation this warlike insect and felt its jealous stab? Every bit as ready to fight as the yellowjacket (I have had both attack when I came within three feet of their nests) , the maculata is generally surer of its aim and swifter to thrust its discourager, thus too often constituting a temporary and local menace. Almost all other social hornets, wasps and bees take their time about striking; even the yellow-jacket will alight and crawl, looking for a favorable place to deliver its sting, but the black warrior strikes and thrusts at the same moment, making no mistake in landing on clothes or hats; she goes at once for bare skin or hair through which she can easily thrust her poniard. Too often she spots the eyes and drives for them.

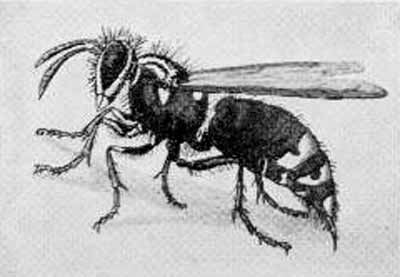

READY TO STING: The black, white-faced hornet

Incidents nearly always more amusing than serious attend the defense of Vespa maculata against its chief enemy, man. It is surprising what enmity is felt toward a creature that is merely defending its rights and also to what extent these little creatures and all the stinging sorority sisters are genuinely feared. I have seen a young soldier who would face bullets and the stones of rioters quail and retreat in haste before one small hornet no longer than the end of his little finger, when it was to his advantage to brave the insects in order to gain valuable time in an important undertaking. I have seen a pugilistic mixer flee before a few hornets as though sure death stalked in his tracks.

The entomologist learns to regard these things more lightly because he has discovered that by deliberate motions and no act that could be construed by the colony as antagonistic he can approach and view their exterior goings and comings without danger.

On top of the often narrow prejudice and fear with which the stinging sorority is regarded it is refreshing to find incidents of the reverse. For though maculata may not often show herself a "friend of man" even though she "dwells by the side Of the road" she really is very beneficial, just as is that other paper nest maker that builds without an external casing. For as catchers of flies and many other pests with which to feed her young these wasps are adept.

In Tuckaleechee Cove on the Tennessee side of the Great Smoky Mountains and at the very foot of Clingman's Dome there dwelt some fifty years ago a respected citizen, Major Tipton, veteran of the Mexican War. As a little lad I remember the hornets' nest that hung in his orchard and was greatly prized by him. Why? The Tipton family ate on an open porch where house flies were normally annoying. But it is well known that these first paper-makers love flies as articles of diet and to feed their tender larvae. To watch a hornet swoop down and seize a hungry fly from a plate, or possibly from the spring-house-cooled butter is a sight that has not been granted to everyone, but if the hornets are plentiful and encouraged the process almost equals fly-screened enclosures.

A PAPER NEST WASP ATTACKS

This also teaches a fact that is universal: unless actually seized no stinging insect will show animosity away from the nest.

Lastly let us consider Bombus. Even the biggest hornets, the most virulent Mutillids, cannot quite equal those ever busy, deliberate, black and yellow, longhaired workers, the bumble-bees, for the amount or the effective strength of the venom which they can put into a wound.

Rather slow to anger, content with their own affairs, the bumble-bees of the many social species are regarded lightly because there are rarely more than two or three on guard at the nest, and not until the abode of the small colony is threatened by actual injury is there defensive retaliation. But when revenge is wreaked upon the aggressor, it is not sweet for him.

Those related solitary forms, such as the carpenter-bee, Xylocopa, and the larger leaf-cutters, Megachile, are quite as poisonous as social Bombus. The manner in which a bumblebee can reach an antagonist or trespasser, catch and cling to a. vulnerable part and apply enough venom to more than satisfy any curiosity upon the subject is something to be long remembered and respected.

What Kipling wrote about the female of the species certainly applies to the stinging sorority. As no male bees or wasps can sting, they make no effort to defend the colony and ignominiously flee on wonderfully swift wings to seek safety. A cowardly act but why try to protect the citadel when such sharp-bayoneted weapons attached to the other sex can so much more effectively gain victory? Why not put the undoubted superiority of the sex usually called gentle to advantageous use?

Printer-friendly version

Printer-friendly version